The Power of Stories, Myth and Nature in London’s Pre-Raphaelite Artwork

- Tess Joyce

- Jan 11, 2019

- 9 min read

Updated: Sep 17, 2019

The Pre-Raphaelites were an inspiring group of artists who sought to reform the field of art in the nineteenth century and offer a window into nature and the soul. Until the 24th February 2018, Tate Britain will be holding an exhibition on the creations of Edward Burne-Jones. I recently had the opportunity to visit and was in awe of his divine artwork as well as the works of William Morris at the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow.

Tate Britain with two giant leopard slugs by artist Monster Chetwynd.

A Pre-Raphaelite and visionary, the paintings of Edward Burne-Jones are rich in symbology, allegory and mythic contemplation. They offer a doorway into the sacred realm of mythology which holds such universal resonance and understanding. The archetypal figures and legendary scenes are like threads which lead us back to the beauty of our true essence and can remind us of a deeper sacred space beyond the chatter of our minds. Burne-Jones believed that his artwork was a window out of the materialism and industrialisation that he felt was diminishing the integrity of Britain at the time and was creating social inequality, pollution and environmental destruction.

It was at Oxford University, whilst studying theology, that Burne-Jones met William Morris and they became life-long friends. In 1856 he abandoned his studies and under the guidance of artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti he began making ink drawings and won the support of many artists in the Pre-Raphaelite circle - it was Rossetti who established the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848 with William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais and he was later joined by other artists including Burne-Jones who shared their artistic principles which aspired to move away from art techniques which were becoming mechanistic and formulaic during that time. In the beginning they had four declarations:

1. to have genuine ideas to express;

2. to study Nature attentively, so as to know how to express them;

3. to sympathise with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and self-parading and learned by rote;

4. and most indispensable of all, to produce thoroughly good pictures and statues.

It was in 1857 that Jane Burden, from a poor working-class family, visited the Drury Lane Theatre Company in Oxford where she was noticed by Rossetti and Burne-Jones who asked her if she would model for their paintings on the Arthurian tales. Later she became married to William Morris and continued modelling for the artworks of Rossetti for many years and they developed an intimate relationship which hurt Morris – yet by many accounts her marriage had grown cold with her husband by that time. Jane became a skilled needlewoman creating many elaborate embroideries. In 1860, Burne-Jones married painter and engraver Georgiana MacDonald and they had three children, Philip, Margaret and a son who died shortly after birth.

Proserpine by Pre-Raphaelite poet and artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1874) – Jane Morris modelled for this painting which was based on the Roman goddess Proserpine whose mythology was closely tied to that of Demeter and Persephone of Greek legends. Proserpine was associated with the underworld of Hades and her mother Ceres was associated with the Springtime growth of crops. Displayed at Tate Britain.

Edward Burne-Jones (left) and William Morris (1874) by photographer Frederick Hollyer

Along with his artist friends, Morris set up the furnishings and decorative arts company Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. which included Edward Burne-Jones, Charles Faulkner, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, P. P. Marshall, Ford Maddox Brown and Philip Webb. Their handcrafted items were medieval-inspired and included stained glass, carpets and tapestries. Morris was a lifelong socialist and environmentalist and I find this circle of artists particularly captivating in their pursuit of beauty, truth and nature amidst the capitalist waves and Victorian industrialisation within the city which had led to overcrowding, disease, pollution and slum housing. Morris was also fascinated by stories and legends, particularly Icelandic sagas, myths and medieval tales.

La Belle Iseult (formerly known as Queen Guenevere) (1858) by William Morris and modelled by Jane Morris. The exhibition of Edward Burne-Jones at the Tate Britain also contained paintings which were inspired by the legends of King Arthur and the following series of myth-inspired paintings were featured at the exhibition.

Merlin and Nimue by Burne-Jones (1861)

There were a few paintings portraying Merlin including Merlin and Nimue (1861) and The Beguiling of Merlin (1873-74.) Both Burne-Jones and William Morris were inspired by writings of Thomas Mallory including Le Morte d’Arthur (1485) which contained various legends about King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. In the above painting, Nimue escaped from Merlin’s sexual appetite by using the magic he had previously taught her and lured him to his end. Normally displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The Attainment, (1895-96) featuring the knight Galahad. In 1888, Burne-Jones and Morris were commissioned by Australian oil and mining entrepreneur William Knox D’Arcy to design and create six tapestries for his country house in Middlesex. The theme for the tapestries was the Quest for the Holy Grail by Mallory.

Edward Burne-Jones and Archibald Maclaren –The Fairy Family. A series of Ballads and Metrical Tales Illustrating the Fairy Mythology of Europe (1857) Burne-Jones and Maclaren developed a friendship at Oxford and Maclaren commissioned Burne-Jones to illustrate a book of fairy stories he had written for his daughter Mabel. Edward created many illustrations, although only three appeared in the publication.

The Lament. A watercolour painted in 1865-66 and the design was inspired by Burne-Jones’s study of the Parthenon frieze in the British museum. It is normally on display at the William Morris Gallery which contains a collection of artwork by Burne-Jones. Although it was not based on a story, the mythological God Pan can be seen on the pillar on the left – conjuring a sense of magic through music as the lady plays her bell harp.

Pilgrim outside the Garden of Idleness (1893-1898) – A painting inspired by Chaucer’s story of courtly love, ‘The Romaunt [Romance] of the Rose’ (c.1390s), which was based on the medieval French poem, Le Roman de la Rose (The Romance of the Rose) by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun. In Chaucer’s retake, the poet dreamed of meeting the God of Love and entered a secret garden with a rose, symbolising the perfection of love, yet he also contemplated the vices outside the garden. The original poem sought to teach about romantic love and the rose was a symbol of female sexuality with the first part of the poem set in a walled garden as a courtier is described wooing his beloved. Normally displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Sidonia von Bork (1860) Sidonia was the main character in Wilhelm Meinhold’s romance novel ‘Sidonia the Sorceress’ (1847) set in sixteenth century Pomerania, (a historical region on the coast between Germany and Poland) about a beautiful witch who destroyed the rulers of Pomerania along with her cousin, Clara. The book was based on historical incidents of Sidonia von Bork who after being dismissed from her role as sub-prioress at the Marienfließ Abbey began to make enemies and was engaged in various conflicts which resulted in the eventual accusation of witchcraft and in many legends she is described as a femme fatale character. Seventy-two charges were brought against her and after torture she confessed. After recanting her confession she was tortured again and finally executed. An unfortunate and unjust ending to this macabre real-life tale.

Love among the Ruins (1870-3) The title for this painting came from Robert Browning’s poem of the same title and it portrayed love as an enduring and pure yet at times, frail force.

The Rose Bower (1880) from The Legend of Briar Rose (1874-1890)

A room of four panels is dedicated to the story of Sleeping Beauty – the scenes portrayed the same moment when the prince entered a realm in which all the people have been bewitched with a sleeping spell. Nothing more is added and Burne-Jones commented: ‘I want it to stop with the princess asleep and to tell no more, to leave all the afterwards to the invention and imagination of people.’ Beneath the painting is the inscription:

Here lies the hoarded love, the key To all the treasure that shall be; Come fated hand the gift to take And smite this sleeping world awake.

Perseus and the Sea Nymphs (The Arming of Perseus) (1877) A whole room in the exhibition was dedicated to the mythology of Perseus. There were many enchanting paintings which really drew the observer into the atmosphere of this epic tale including this portrayal of the Nereids (sea nymphs) who gave Perseus the equipment he needed to conquer over Medusa which included the helmet of invisibility, winged sandals lent by Hermes allowing him to fly and a magic pouch, (‘kibisis’) to contain Medusa’s head.

The Death of Medusa (I) (c.1882) This painting portrayed the act of killing Medusa and the consequent birth of her two children since she had been pregnant at the time. Chrysaor and the winged horse Pegasus were the sons of Medusa and Poseidon and were conceived in a temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva.

The William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow is also worth a visit and contains many pieces of art, tapestries and stained glass by Morris, Burne-Jones and their company. The building of the gallery was the house where Morris lived as a teenager and he was born in Walthamstow East London in 1834.

The William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow.

At the age of six, Morris and his family moved into Woodford Hall on the edge of Epping Forest which had a 50-acre park where Morris had his own Shetland pony and patch of garden. The hall was demolished in 1900. Morris was very inspired by the Essex countryside around him and he was able to identify many plants, birds and flowers – designs from nature influenced his work and he advised his designers to use abstract patterns influenced by nature rather than copying literally. He liked the patterns to be strong with an ordered structure. Epping Forest is a beautiful oasis for London dwellers to visit, full of hidden groves and an earthy peace.

Photos from Epping forest in January 2019.

For some more recent artwork inspired by Epping Forest please see the website of artist Rachael Lillie. The forest is full of Iron Age imprints such as Loughton Camp, (an Iron Age hill fort) and a quern (Iron Age grain millstone) can be found nearby. https://www.rachel-lillie.co.uk/The-In-between

Wandle furnishing fabric by William Morris, late 19th century. Morris was particularly inspired by the River Thames and its tributaries and abstract passages of water can be seen in some of his patterns.

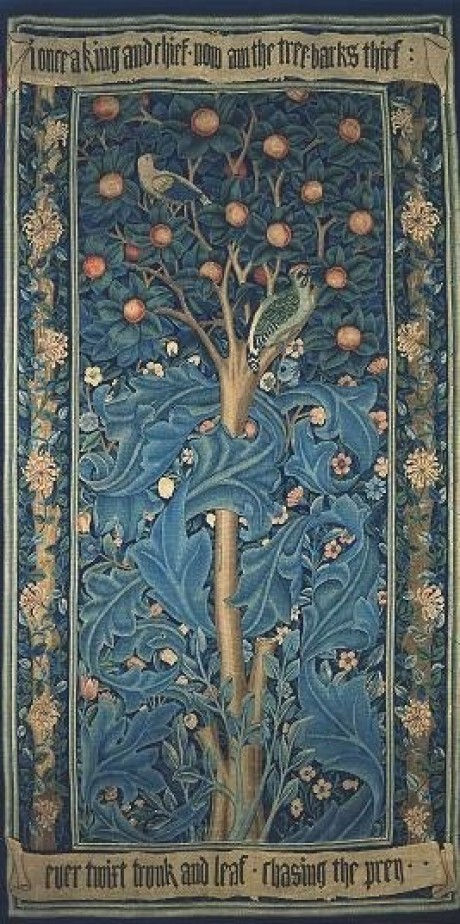

Woodpecker Tapestry (1885) This tapestry was inspired by a tale in Ovid’s Metamorphoses in which the King Picus is turned into a woodpecker when he refuses the love of the sorceress Circe.

Morris was also a writer and in 1865 he started writing his famous book, The Earthly Paradise which became a bestseller. It was a poem about a group of Nordic travellers who were looking for paradise and ended up on an island where descendants of the Ancient Greeks lived – each month, the two groups would gather and tell stories and he retold twenty-four of his favourite tales within the book including the legend of Cupid and Psyche. Burne-Jones made the drawings to illustrate this legend and medieval-style woodblocks were used including one made by Elizabeth Burden, Jane’s sister.

Jane Morris in Medieval Costume, by William Morris (1861) – in this study for a painting, Jane was cast as Helen of Troy and it is most likely that she made this costume herself.

Jane Morris, the wife of William Morris (1865) by photographer John Robert Parsons. They had two daughters, Jenny and May who both became embroiderers.

William Morris and Rossetti had a joint lease for Kelmscott Manor and Rossetti often painted the Morris women at the house during 1871 to 1874. Rossetti had relationships with three of his muses, Jane Morris, Fanny Cornforth and Lizzie Siddal who he eventually married in 1860. Their relationship spanned a decade but she eventually died from her addiction to laudanum with an overdose in 1862 - may she be at peace.

Sir John Everett Millais's Ophelia (1851-52) Lizzie Siddal was the model for this painting of Ophelia from Shakespeare's play Hamlet. Millais was one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Inspired by Icelandic sagas, William Morris also retold the tale of the warrior Sigurd the Volsung in a poetic version and his daughter May once stated that this was the book “he held most highly and wished to be remembered by.” He didn’t travel much however in the early 1870s he visited Iceland on ponies with his friends and admired the unpolluted landscape of rivers, lava fields and icy mountains.

In later years Morris became a prolific socialist and environmentalist and at one stage was doing up to three talks a day. He was particularly enamoured with the nearby Epping Forest and he campaigned to protect the hornbeams in the 1890s which gave the forest so much character. “We want a thicket, not a park, from Epping Forest,” he once remarked. He also campaigned to stop pollution in the River Thames and he called to protect the countryside. For Morris, beauty was synonymous with nature.

Comments